What makes a book compelling? Join me in reading good books and honing the craft of writing.

IT’s Free, so Subscribe and Enjoy!

In mystery novels, readers are led to wonder: What happened? The story moves forward by looking backward.

Readers well know the lab folks do their thing on crime scenes: taking pics of blood spatter, knocked down furniture, spilled wine glasses and, of course, dusting for prints. With careful dusting, formerly hidden fingerprints come into view, complete with their ridges and swirls, and their no-two-are-alike patterns.

The glass window in the picture above contains fingerprints, some visible, some latent, courtesy of the light. Whose they are shall remain a mystery, since no one freely confesses to smudging windows.

I’ll confess I’ve read Elliot Ackerman before. Ackerman picked arguably the toughest branch of service, the Marines, and served five tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. He earned the Silver Star, the Bronze Star for Valor and the Purple Heart.

He’s written a number of books, including co-authoring a thriller, 2034: A Novel of the Next World War. 2034 was my introduction to Ackerman. I was doing research into a novel set in Asia and his book made its way into my stack.

Ackerman’s personal experience has impacted his views of foreign events, including our chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan, a place he not only fought but lost friends. Here’s what he wrote in his 2019 bestselling memoir Places and Names about whether he regrets his service:

When you are a young man and your country goes to war, you’re presented with a choice: You either fight or you don’t.

I don’t regret my choice, but maybe I regret being asked to choose.

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal[1], he distinguished modern conflicts from generation-defining events such as world wars:

When you’ve got wars with an all-volunteer military funded through deficit spending, they can go on forever because there are no political costs.

[1] https://www.wsj.com/articles/elliot-ackerman-went-from-u-s-marine-to-bestselling-novelist-fc5705ca

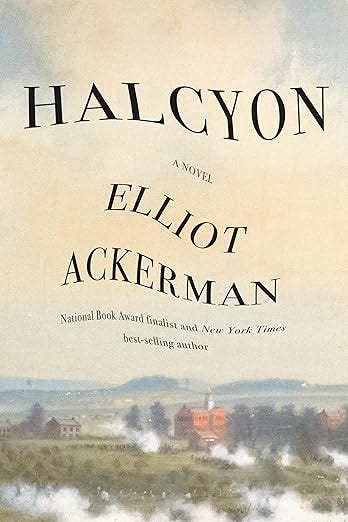

Clearly, Ackerman has much to say. So it was with great interest I picked up his newest novel. Halcyon is about history and our fluid perceptions of the same, a fitting topic for the times. The past is the past, and nothing can change it, right? The American colonists under George Washington defeated Britain on the battlefield at Yorktown and eventually won independence (a fact for which Britain is ever-so-grateful since we baled them out in both World Wars). More relevant to Halcyon, the South surrendered to the North, ending the Civil War and reuniting the country (for a time anyway).

Halcyon—Ah, golden days gone by. Hard not to feel warm and fuzzy.

Not quite. The Civil War especially continues to divide us. Examples include tearing down Confederate monuments and renaming Army posts, such as Fort Hood in Texas, now Fort Cavazos, to sever connections to the Confederacy.

The fluidity of history is illustrated in the cover art. The title and author’s name appear as if underwater, and a battle scene is hazy from cannon smoke and something else.

As you wade into the story, my suggestion is attend to not just what’s in front of you, but what’s on the flanks. Halcyon contains much latency that becomes apparent.

The narrator, Martin, is on a sabbatical from teaching history in college, working on his nonfiction book about the Civil War. It’s the early 2000s, Gore is President, and Martin is staying at a Virginia estate. He gets to know the owner, Abelson, a man of considerable reputation and a war hero. Martin struggles with his book, as it built upon a theory, the “great compromise,” put forth by Shelby Foote, a real historian. The theory posits a cultural reconciliation between the North and South after the war, allowing the South to hang on to the righteousness of its cause. Martin’s problem is the theory now has fallen out of favor by his university. He’s not PC.

Martin ponders his predicament:

. . . I had become obsessed with the role of compromise in the sustainment of American life, as well as our relatively recent departure from it as an American virtue. I had my theories on what contributed to our current plague of polarization: gerrymandering, the shifting media landscape, campaign finance laws; however, identifying the causes wasn’t enough, it would do nothing to ease our grim national mood, which I would have diagnosed as rage-ennui. . .

Oh man! Talk about inner thoughts as someone tries to figure out what’s going on! I’m rooting for him, especially in an election year.

The other thing worth noting from this passage is how academic Martin is. And we all know academics have reputations of being isolated in the Ivory Tower. Can he overcome this, come down to earth where the rest of us live?

In true academic fashion, the above paragraph continues into a lengthy, but enjoyable stretch:

. . . I had once shared these views with Abelson [his landlord], who through the wisdom of his many years identified a different source of America’s blight. “Sex,” he’d said, “the conflict between the male and the female, it is the conflict from which all others derive.” He was, of course, referring to our recently disgraced president. When I said as much, he made a little negative wave of his hand. His reference went far deeper than that, traveling backward well beyond Clinton or even my specialization, the Civil War. “The ancients fought about Helen of Troy. We fight about Monica Lewinsky. It’s all the same; it’s all sex.”

I couldn’t hold it in, had to laugh out loud.

To get to where he’s going, Ackerman uses several devices, some which bend the book well beyond its commercial fiction genre. And in so doing, he takes a bold artistic swing for the fences.

One such device is a bit of SciFi. Many alternate history novels are cast as SciFi when they’re only minimally so. Here, a new discovery prolongs human life by cell regeneration. Abelson is an early recipient, a willing guinea pig, of the procedure. It allows Abelson, who’s elderly when the story opens, to remain as the protagonist, as the living history who undergoes revision.

Once I understood this, the frontispiece art of a DNA strand made sense; it originally caused confusion by seemingly clashing with the battleground scene on the cover. Ackerman begins with this cell regenerative discovery. It left me foundering for a bit as I tried to get my feet on the ground inside the story. I almost wish he’d taken some time to ease the reader in by letting us grow comfortable with Martin and Abelson first. No matter, because Ackerman makes it work.

Another such device is using the academic Martin as the narrator, instead of Abelson, the protagonist. Much like the hazy cover art, it allows Martin some distance from what’s going on in Abelson’s extended life. Since much of the action concerns Abelson, it almost seemed too distant, until I realized Martin can’t take part; he’s an historian, not a witness, and necessarily must look at the stories of the past from afar.

And then, there’s an absolutely brilliant scene at the end, where Martin travels to visit a place and there is some clean up. I can’t say what kind of place, other than it’s inside, otherwise, it’ll lessen the impact. My reaction was Oh Yeah! It snuck in, unexpected. I’d rank it at the top of my list of novel closings as it put the ribbon on the package Ackerman wrapped for us.

Read it so you can later enjoy the halcyon days of a brilliant book discovered. Let me know if it moved you as much as it did me.

Are there any histories you’d like to rewrite?

Alternate history books have long been revising the past for our pleasure. Many use science fiction.

In Machines Like Me by Ian McEwan, Britain has lost the 1982 Falklands War. As the country deals with the fallout, a love triangle forms between Charlie, Miranda and a first gen synthetic human, Adam. In which we wonder what it means to be human?

Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America was written twenty years ago, but has heightened relevance today. FDR is defeated by Lindbergh, an outspoken isolationist. Antisemitism isn’t isolated to Nazi Germany, it finds fertile soil in America.

Rodham by Curtis Sittenfeld twists history, making some wonder what might have been. Hillary dumps Bill (the reasons are already known by all) before becoming a Clinton and makes her own way. Will she run for President?

Favoring the academic approach, James Banner wrote The Ever-Changing Past: Why All History is Revisionist History. Its title sounds like a plea by a historian for job security.

Novels using narrators other than protagonists are uncommon, but can be effective. Adam White's debut mystery, The Midcoast is one.

Set in Maine, Andrew, a high school teacher, returns to his hometown. Things have changed, including the new wealth of the Thatches, neither of whom made the Most-Likely-To-Succeed list in high school. Can the Thatches withstand allegations of murder? White says when he wrote the book he hand in mind The Great Gatsby, where Nick narrates the opulence and downfall of Jay Gatsby.

All the Best,

Geoff

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the heart “❤️” so others can find it. It’s at the bottom and at the top.

Good job Geoff. Always enjoy your take.