What makes a book compelling? Join me in developing our “Eyes and Ears” for finding compelling stories.

Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North is a remarkable story about Australian POWs caught up by love and war. Is it a subversive novel?

We’ll talk about the book first before getting to the question. We’ll do so in a manner that emulates the chronological/topical mashup of the novel.

Two Books, Same Title

Dorrigo Evans is the protagonist surrounded by an ensemble cast that broadens our view of World War II and the thereafter. Flawed before the war, Dorrigo embarks on unwilling travels into the Deep North along the Burma railway as a POW doctor powerless to help his fellow soldiers endure the hellish conditions. Before he ships out to war, Dorrigo becomes informally engaged to someone he’s not terribly excited about and falls for another, namely his uncle’s wife. Sparks fly, romantically and otherwise, events that resonate throughout the story.

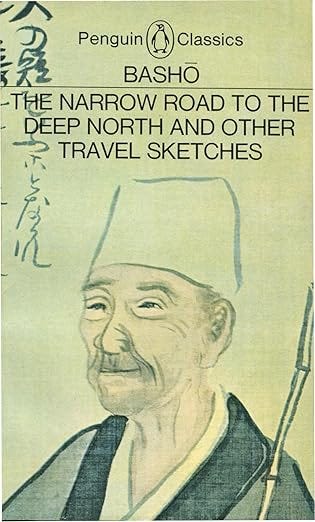

When I ran across the title, I thought, Wait a minute, haven’t I heard of that before, only in a different book?

Yes, because it’s the same title as a 350-year-old book by Bashō, a Japanese poet. Same title, completely different books. Bashō’s tale is a travelogue of his trip north out of Edo (Tokyo) into the wild and wooly interior and along the west coast. He mostly walked and occasionally rode horses, all through mountainous terrain. Bashō wrote in haibun, a combination of prose and haiku. Haiku is like flash poetry in that it’s short and gets to the point. Because it’s short, it’s easy to miss the point.

Bashō’s prose strives to set up his poems. Some make sense to a modern mind. Some don’t. Had he lived and poetized today, he might have written:

Crested the interstate hill

Exited to a Starbucks

Looking for a caffeine jolt

First in line in the Drive-Thru

Feel the rejoicing of not having to wait for your drink of choice? If you didn’t, you might find Bashō to be understated. You might wish for more directness:

Crested the hill doing 70

Swerved to make the exit after seeing the Starbucks sign

Needed to stay awake

Ran the yellow to beat the other guy to the Drive-Thru because didn’t wanna wait in line

Hell yah.

Neither poem is Bashō, the latter not even close to his style.

Anyhow, because he celebrates old Japan (you can tell he’s centuries old because Bashō doesn’t bash his culture), Bashō is apparently regarded as a cultural hero in Japan. Col. Kota certainly thought so. Kota is a fictional character in the novel. He oversees Japanese POW camps in Siam/Thailand, and comes to visit the one where Australian POWs are not just held, but imprisoned in contravention of every Geneva Convention rule. In WW2, if you could take your pick, captured by the Germans or by the Japanese, and granted it’s a big choice almost nobody had, you’d pick the Germans hands down because they treated prisoners of war much better, humanely even. Unless you were Jewish. The Japanese saw every POW as Jewish-like and treated them as animals barely worth the rice ball they received as daily rations.

Here is Bashō giving us the flavor of traveling in feudal Japan [with my brief haiku-like comments for clarity]:

. . . [I] arrived by way of Naruko hot spring at the barrier-gate of Shitomae which blocked the entrance to the province of Dewa [located several hundred miles north of Tokyo/Edo]. The gate-keepers were extremely suspicious, for very few travelers dared to pass this difficult road under normal circumstances. I was admitted after long waiting, so that darkness overtook me while I was climbing a huge mountain [that stinks]. I put up at a gate-keeper’s house [another gate-keeper? How many are there? Where’s the interstate?] which I was very lucky to find in such a lonely place. A storm came upon us and I was held up for three days.

Bitten by fleas and lice,

I slept in a bed,

A horse urinating all the time

Close to my pillow.

The prose sets up the poem, a short glimpse into that stretch of his travels. Fortunately, Dewa no longer exists as a province, having bit the feudal dust.

Here is Flanagan’s take from the POW camp, whose starving, malnourished Australian soldiers are enslaved to build the Burma Railroad through inhospitable jungle and mountains, where it rains all the time. One of those prisoners is Darky Gardiner, so nicknamed because he’s half white, half Aborigine. Much like Dorrigo’s story playing off Bashō’s book, Gardiner is a character whose presence resonates throughout the story against Dorrigo. The excerpt below is one of the darkest moments in the book; it’s included here because it’s relevant to the question of subversiveness, so stick with it. Gardiner ate a smuggled duck egg in the wee hours of night to stave off his gnawing hunger.

By now fully awake from the pain that gripped his abdomen, and panting with the intense effort of walking without shitting himself, Darky was still some way from the benjo [latrine] when he slid off the greasy shoulder of the path and into its muddy centre, up to his ankle in filthy mud. He momentarily panicked. His sudden, frantic effort to get back up on firmer ground excited his bowels. He felt an abrupt loss of extreme tension and, with a relieving rush, realized he was shitting himself in the middle of the camp’s main path.

Bashō’s poem above is an exception as most aren’t scatological, but aim for a higher being. Here is an example, where Bashō ventures behind a temple to see the remains of a priest’s hermitage, a tiny hut propped against the base of a rock, a scene that moves him to write on the spur of the moment:

Even the woodpeckers

Have left it untouched

This tiny cottage

In a summer grove.

It probably helps to have been there.

In Darky Gardiner’s case, Flanagan paints the scene so well, we’re glad we weren’t there. Dorrigo has to live with it and how he manages is what makes for a remarkable story.

Flanagan’s novel is well worth a read.

Is it Subversive?

Dorrigo enjoys poetry. So too does Col. Kota, who fancies himself as cultural because of his tastes. Yet, while Dorrigo is a doctor trying his best to heal, Kota is a human piece of scat. There are other ways of saying it, but we’ll stay with scat. Prison officials and guards make easy antagonists but these guys, Kota and the others, go beyond the pale, acting with historical accuracy in their debauched treatment of the prisoners working on the Burma railroad, a Japanese military boondoggle if there ever was one. They made the prisoners work in inhumane conditions, with starvation rations, near-nakedness, virtually no medications or interest in keeping them healthy. If they died, it was one less mouth to feed, all in the glorious name of the empire.

Christianity was subversive in taking the cross, a Roman tool of painful, inhumane execution and turning it into a symbol of love and hope, of second chances. Flanagan’s novel parallels Bashō’s work of travel to find one’s meaning in life, with Dorrigo’s, his fellow Australians’ and the Japanese captors’ travels through life during and after the war. Bashō’s work is so revered, people today replicate his route through northern Japan. Flanagan, whose own father was a POW on the Burma railroad, takes a national treasure and rips it to shreds by the country’s own actions.

He does so to remind us of the utterly frightening possibility that any country, no matter how cultured they think of themselves, can be driven by fanaticism and quickly devolve into inhumane scat or whatever else you wanna call it.

Speaking of reminding, we’re due for a novel subverting Russia’s beloved love story in war, Doctor Zhivago, this time told from a Ukrainian hospital under Russian missile bombardment or similar circumstances.

All the Best,

Geoff

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the heart “❤️” so others can find it. It’s at the bottom and at the top.