TRIALS BY WRITING

What makes a compelling book? Join me in reading good books and honing the craft of writing.

Why Trials By Writing?

Writers, especially emerging writers, love to join the crowd and beat ourselves up. But there’s more to it, isn’t there?

Welcome to Trials By Writing, a look at the many obstacles and sparsely strewn rewards of a career in writing. Well, sometimes a look. Sometimes a hyperventilation. Frequently an admiration of those who have not only gone before, but have done so with exemplary skill.

If you’re a writer, or considering the same, keep reading. If you’re a reader looking for good books and want to see how the sausage is made, or enjoy farm-to-table/ink-to-paper fare, keep reading.

Before deciding to try my hand at fiction writing, I’d worked in a couple of creative and intellectually stimulating professions. I’d written and edited millions of nonfiction words, much of which was closely scrutinized. Try my hand turned out to be a much-too-casual approach to a demanding craft. My character arc involves repeatedly discovering writing fiction is a different animal. Writing fiction isn’t just an animal, it’s a beast. I’ve always read fiction, but I hadn’t grasped readers are finicky.

Writing is an art, and art is a lot of trial and error. I’ve discovered the beastliness after writing several non-casually written novels, novels I wrote and rewrote, and submitted to a slew of agents. So far, my fiction writing story parallels The Life and Times of Wile E. Coyote. He (me) constantly chases the roadrunner (a traditional book deal), devising fiendishly clever schemes (plots, genre-bending, etc.)- dropping an anvil from great heights onto his prey, laying a trap with TNT and so on.

At this point in the post, I’d love to drop in a cartoon pic of Wile E. roped to the outside of a rocket, set to chase his much faster prey. I won’t because the pic is copyrighted. But I’ll describe it: As the roadrunner zooms past, the coyote holds the lit match, not to the fuse, but to his tail, setting it on fire. Yep, I’ve burned myself a time or two in this thing called a writing career that so far is in name only. “I’m a writer,” I tell my family, without a book contract to show them. “Yeah, sure dad,” echoes the response.

After each fail, each, for lack of a better word, R–, I study my navel, stand on one leg murmuring mantras and try to rebalance the universe that is so horribly out of whack as to not publish my book that I’ve sweated over . . . .

NO! I don’t do any universal rebalancing. The universe is too big. Call me dumb, or ignorant, or just plain tilting-at-windmills-crazy, but here’s what happens next. I wake up early, teeming with excitement. I try to be quiet and not wake anyone else, although stumbling around in the dark occasionally leads to, well, you know, noise—an ouch or an oof or something clatters to the floor. And I start a novel or a short story. I do it because . . . .

I once ate a book by Alan Moorehead titled Cooper’s Creek. Devoured it word by word, chapter by chapter. It’s been years, and I haven’t so much as browsed another book by Moorehead, but I still remember his name, that’s how satisfying the book went down.

Our family enjoyed a rare string of a few of days where the roads were so iced the office closed and city-wide, we were all stuck at home. Although this was back before work-from-home became a thing, it was during the era when work-at-home was the necessity for someone building their law business. I always carried work home for evenings and weekends.

But during this string of days, I did something unusual. I took the days off, even though when the office reopened, the pile of untended work would be tall weeds. We played with the kids, marveled at how ice built up on the inside of the single-pane windows. The ice thickened along the bottom of the panes of the double-hungs and I worried about the melt water penetrating the peeling paint and swelling the wood muntins. I meant to scrape, prime and repaint those muntins, which possessed so many curves and grooves it would have taken forever. Instead of scraping and painting, I took the kids outside to slide on the ice and experience the cold, and after only a short span of time, ushered them back in to keep warm since they, like me, are true southerners with little tolerance of low temps.

And then they played. By themselves. Between meals. I took full advantage by snacking on Cooper’s Creek.

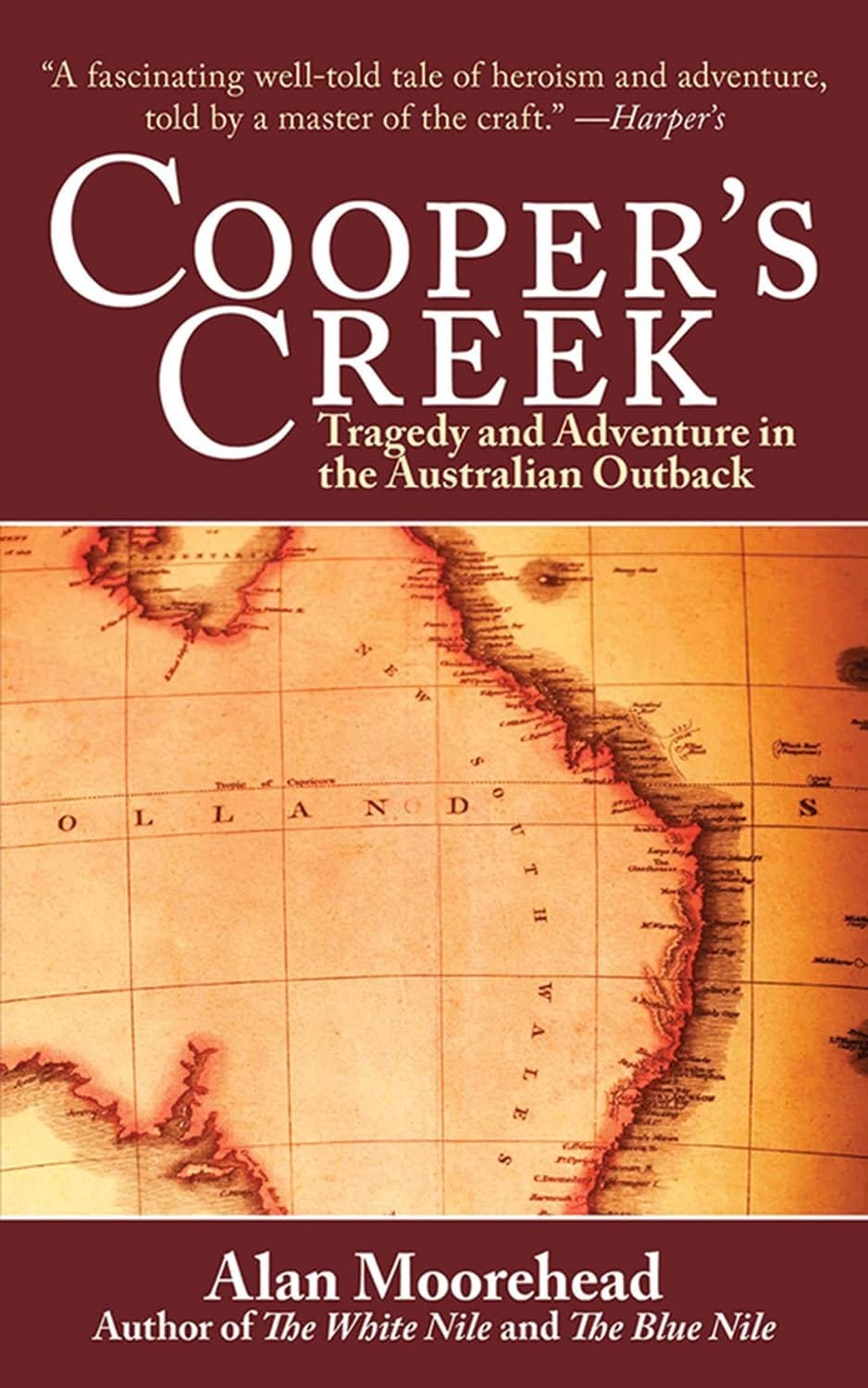

The Burke-Wills expedition aimed to be the first to cross the interior of Australia from Melbourne north to the Gulf of Carpentaria, a distance over 1500 miles, or about the distance from Dallas to Southern Oregon, only in Australia, the interior is mostly desert.

Relying on a mixture of camels and horses, they embarked in 1860, the same year our Civil War began.

Cooper’s Creek (now called Cooper Creek) lies about halfway along their route. There, the expedition split their party, leaving a base camp contingent, and sending a smaller, faster, exploration team on to the Gulf.

What turned from a snack into a feast and held me during those moments of the ice storm, what made me avoid the TV playing movies for the kids, what captivated me to the point of almost missing meals was Moorehead’s vivid description of the expedition struggling with the Australian outback elements of heat, aridness and little food. Cooper’s Creek was both an oasis and a trap to any expedition that exhausted its supplies. It provided water and some edible native plants, but unbeknownst to the explorers, the plants alone couldn’t sustain life.

Cooper’s Creek came to mind as I thought about initiating Trials By Writing. Like the expedition members, in fiction writing, I possess unbridled optimism, brought about from ignorance of the difficult conditions writers face. Like the expedition members, I’ve suffered from the lack of communication. The base camp members departed Cooper’s Creek for resupplies, but carved less-than-clear instructions on a tree for the returning explorers. The returning explorers, weakened by their arduous travels and exhausted of supplies, didn’t know they missed the departing base camp team by hours.

Instead of pursuing the base camp members, the explorers remained at Cooper’s Creek, with the deceptively edible plants. They slowly starved. Only one survived, saved months later by a rescue party, but he didn’t regain his full health and died at the age of thirty-three. Agents and publishers rarely provide any meaningful insight into why they’ve rejected a work, or what it is they’re looking for. Yeah, you rejected the submission, but how close was I?

But why write? Why venture into the voids of publishing that are larger and drier than the Australian outback? Why not learn from Burke-Wills and just stay home, leaving the writing to others? Why do I keep acting like Wile E. Coyote and fall off the cliff, splattering on the canyon floor, why stay the course only to be crushed by the dropping anvil, which anvil is of-my-own-making, why disintegrate when the TNT explodes? Believe me, it’s not to entertain my family or friends. All that stuff hurts.

Lots of answers, really. Here’s one: I think it’s to return the favor of authors. Like the favor Moorehead gave me during those magical, ephemeral days when the kids were young enough to toss in the air, climb on my back and I not only broadened my world view by traveling to another place, another time, but waded smack into human tragedy. Armed with a close encounter of loss, I played with the kids a little longer, hugged them a little tighter.

Besides, despite my Wile E. Confidence, with each fail, I tell myself I learn something new: from big picture character arcs, building suspense to the small grit of sentence structure. Sometimes the learning curve steepens, sometimes it flattens, but the road goes on.

The good news, I’m not the first to slog down this path. Kathryn Stockett, author of The Help, says she was rejected sixty times.

Ah, what’s a few dozen? I recommend reading The Help, even if you’ve seen the movie. Her shifting points of view among the three women, one white, the other two black, her use of conflict with the maids risking their livelihoods in a small town to tell their story, is a book we writers can learn much from.

So, splattered and crushed by the falls over the cliff, maybe I’ll brush up on nuts and bolts grammar. Concussed by the anvil, maybe I’ll better structure my story next time. Deafened by the explosions, maybe I’ll clear the fog and hear what others listen to when they read my work. I’ll keep crafting stories because I cannot not chase the blankety-blank beep-beep.

Enough about me. What I want to know is what about you? Why do you endure writing?

All the Best,

Geoff

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the heart “❤️” so others can find it. It’s at the bottom and at the top.

The publishing industry has also changed so much in the last 15-20 years or so and I know that so many writers relate to this journey. Gone are the days when an agent or publisher saw a tiny spark of something and picked up a debut author and worked with them till it was right. The industry now requires fully published works that are ready to go... Or have a name to yourself and know that your work will sell.

I hope for you that you do not give up and keep writing. ☺️

Thanks Geoff. Copper’s Creek sounds like something Cormac McCarthy would have written: stark, blunt, no happy ending. That’s the way it was!

My great, great, great, great, great grandfather homesteaded in Kansas in 1870. By fencing 160 acres and surviving one year he owned the quarter section: 160 acres. In a cemetery a half mile away is a stone marker for a little girl that died when she was kicked in the head by a horse on a wagon train. It’s the first marker and established the cemetery where all my paternal grandfathers are buried and my mother.